In 1769, Lieut. James Cook sailed to Tahiti to record the Transit of Venus, an astronomical phenomenon that would help to determine longitude. The second part of his mission, partly funded by Botanist Joseph Banks, would also send them to Terra Australis Incognita, the Great Southern Land, which under the King’s orders, Cook would claim for the British in 1770.

Banks, along with his small team of botanical artists, encountered and recorded hundreds of floral species on the voyage that were new to European eyes. Banks’s aim was to publish a collection of engravings for enthusiastic European collectors who were hungry to learn about flora from the New World. However, Banks wasn’t able to achieve this in his lifetime. The first reproduction of the 1770 artworks, Banks’s Florilegium, was published in the 1980s.

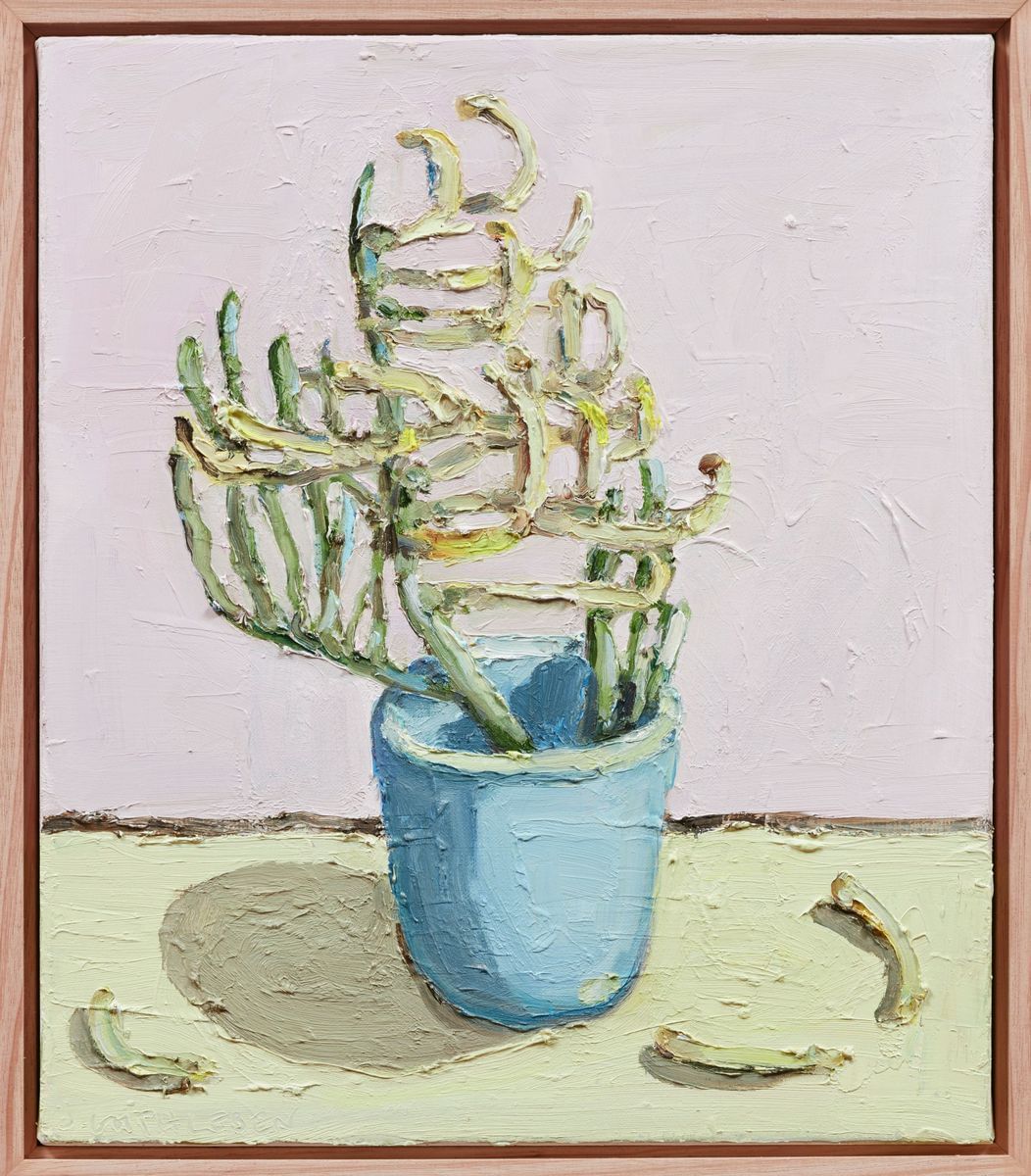

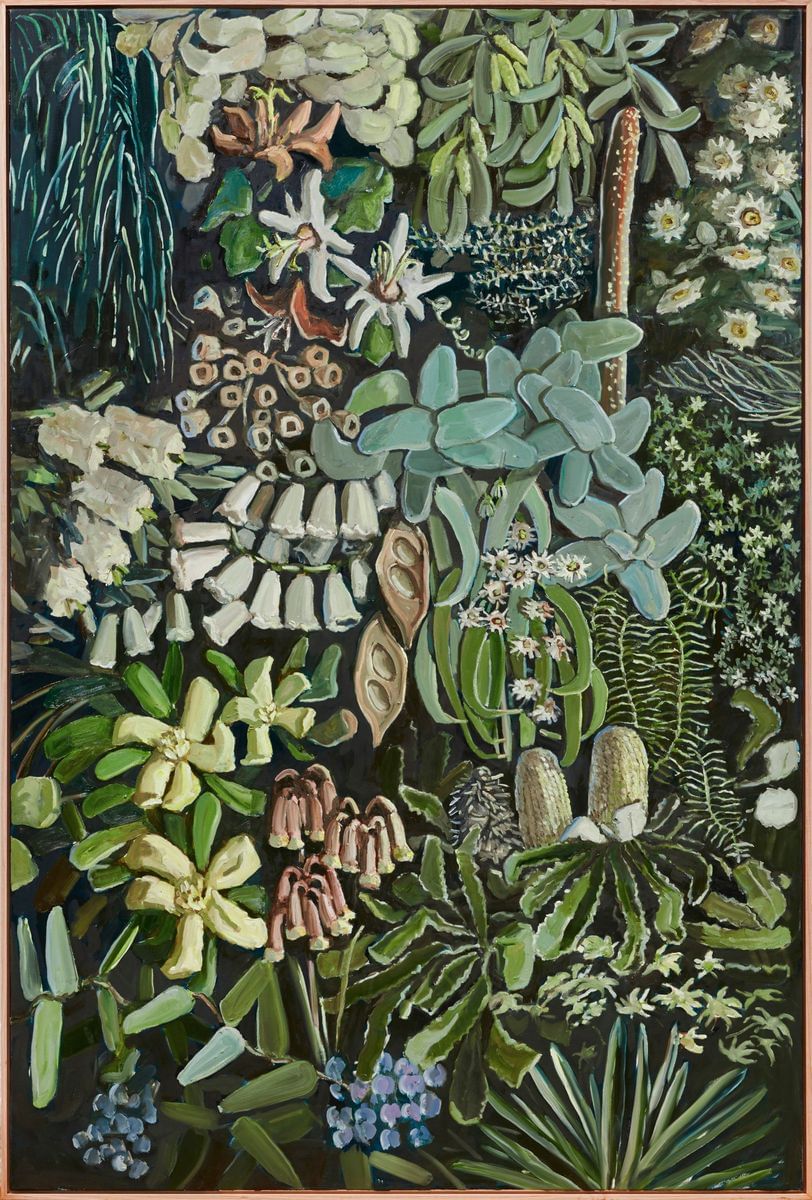

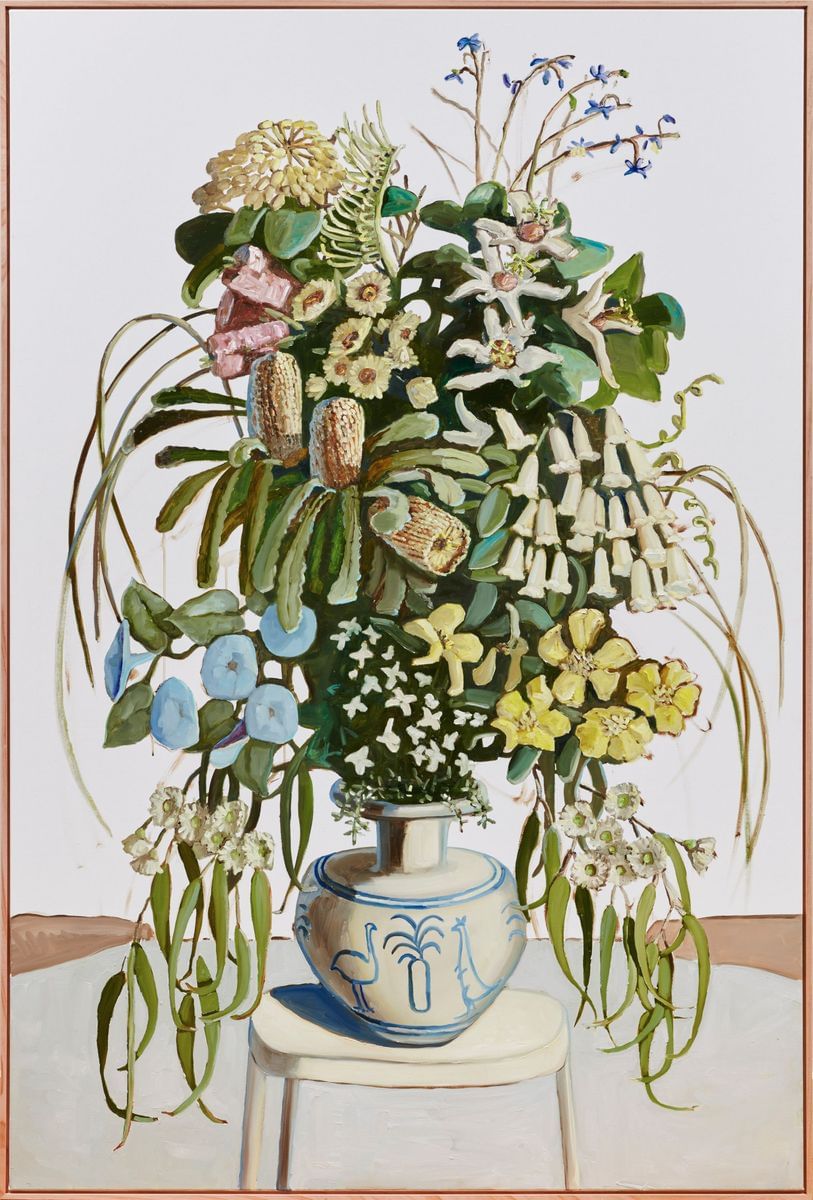

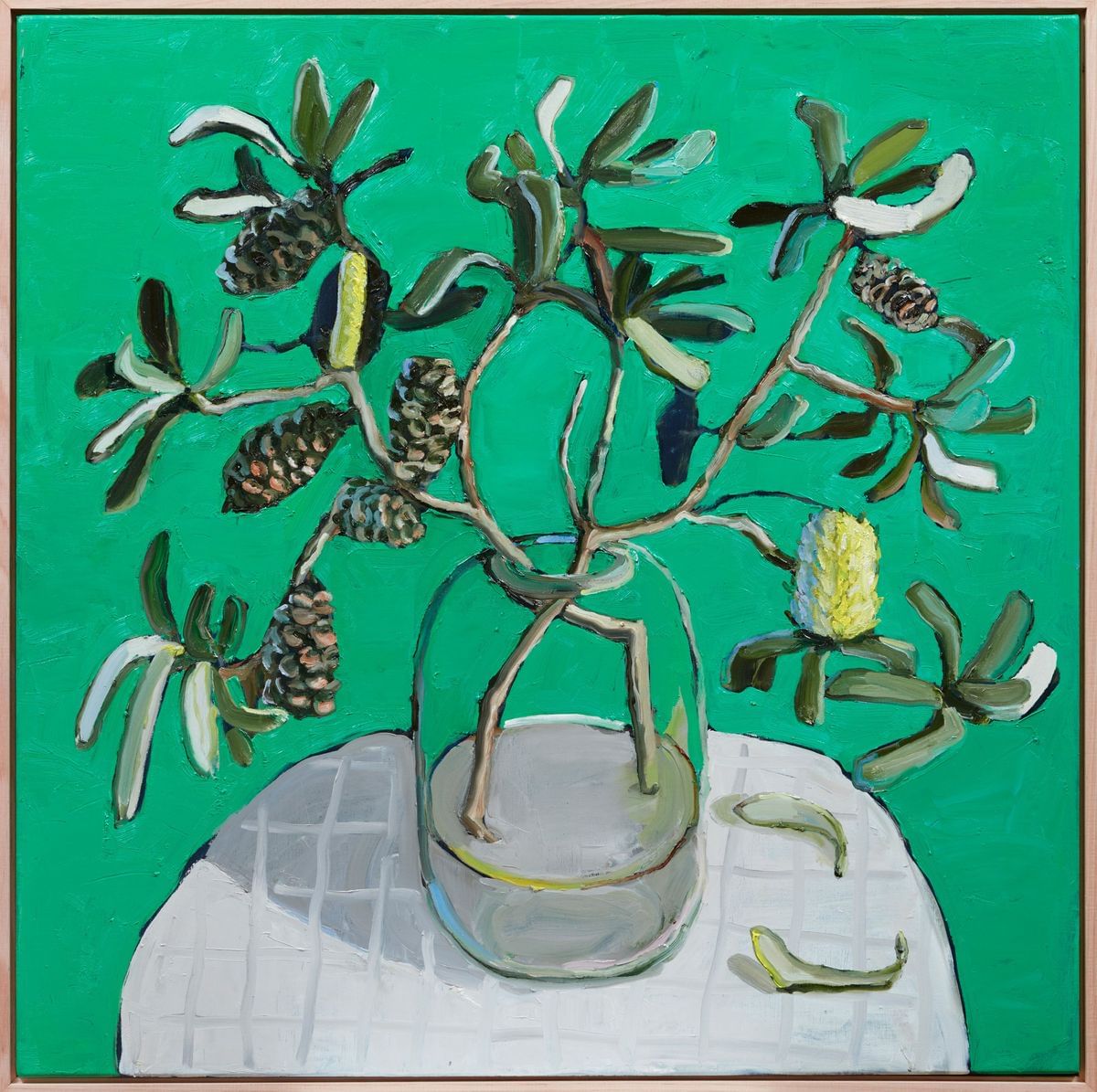

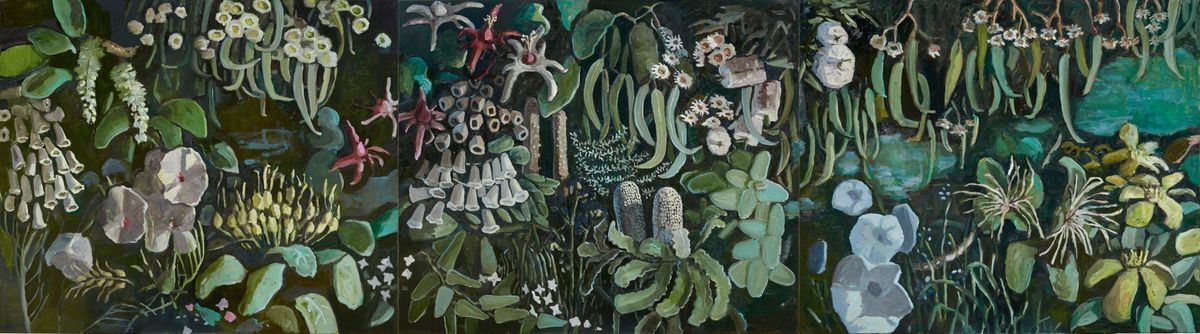

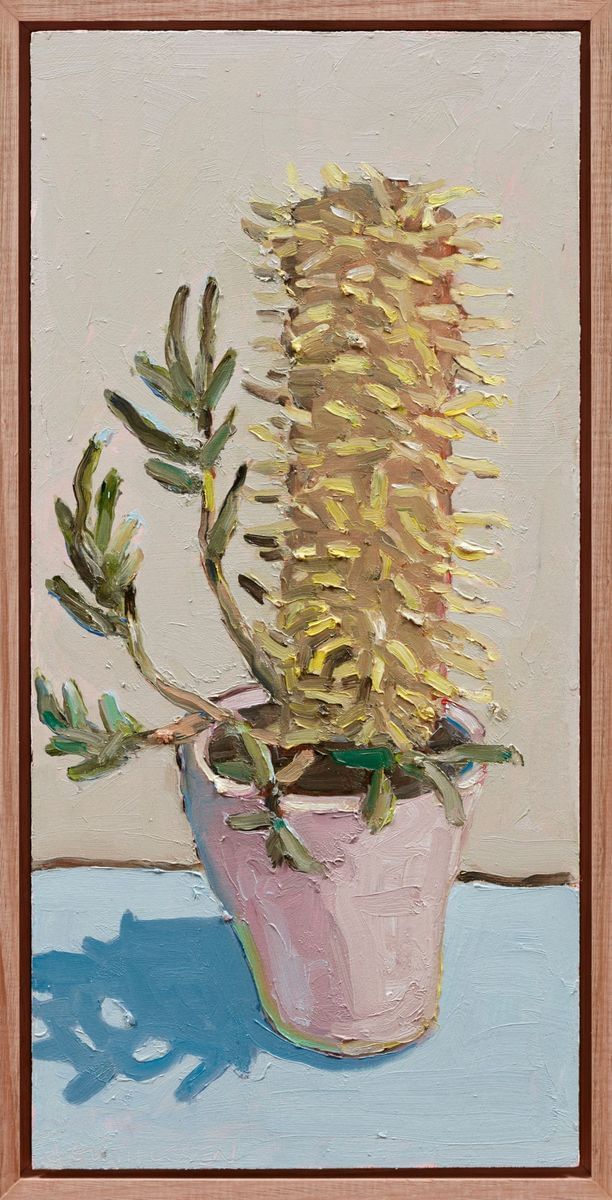

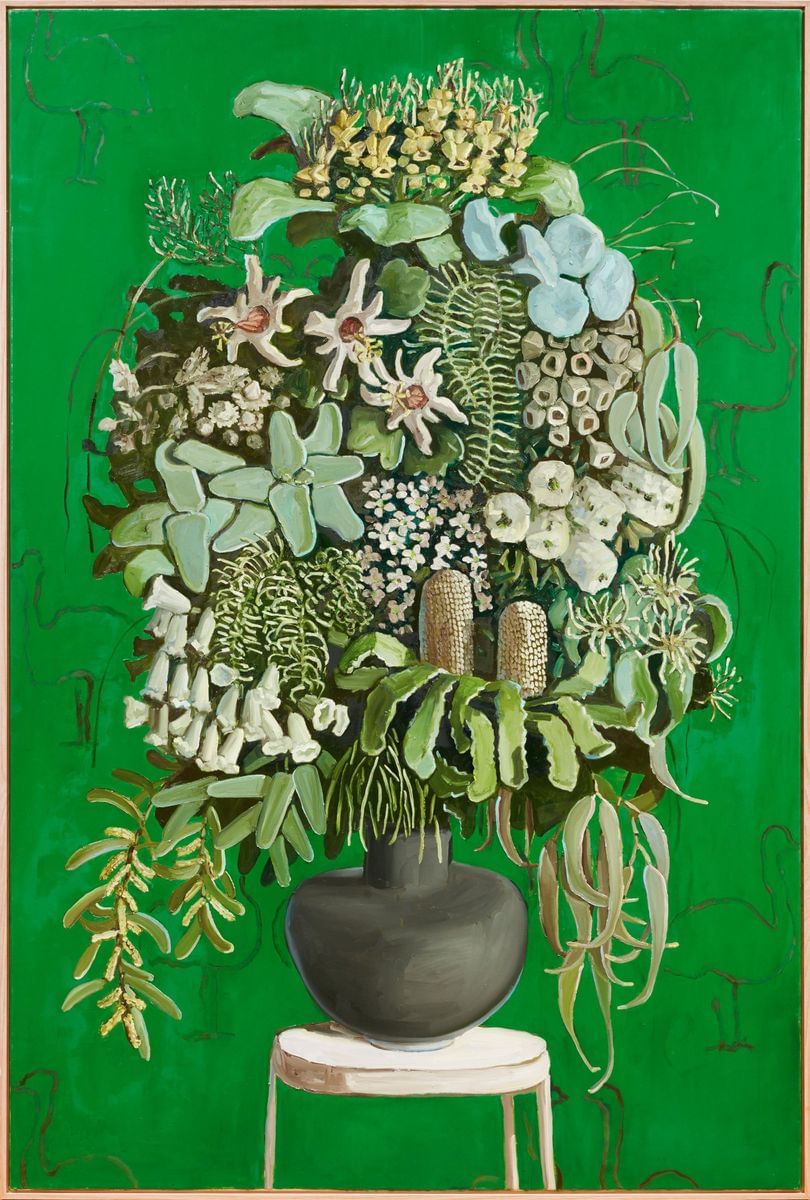

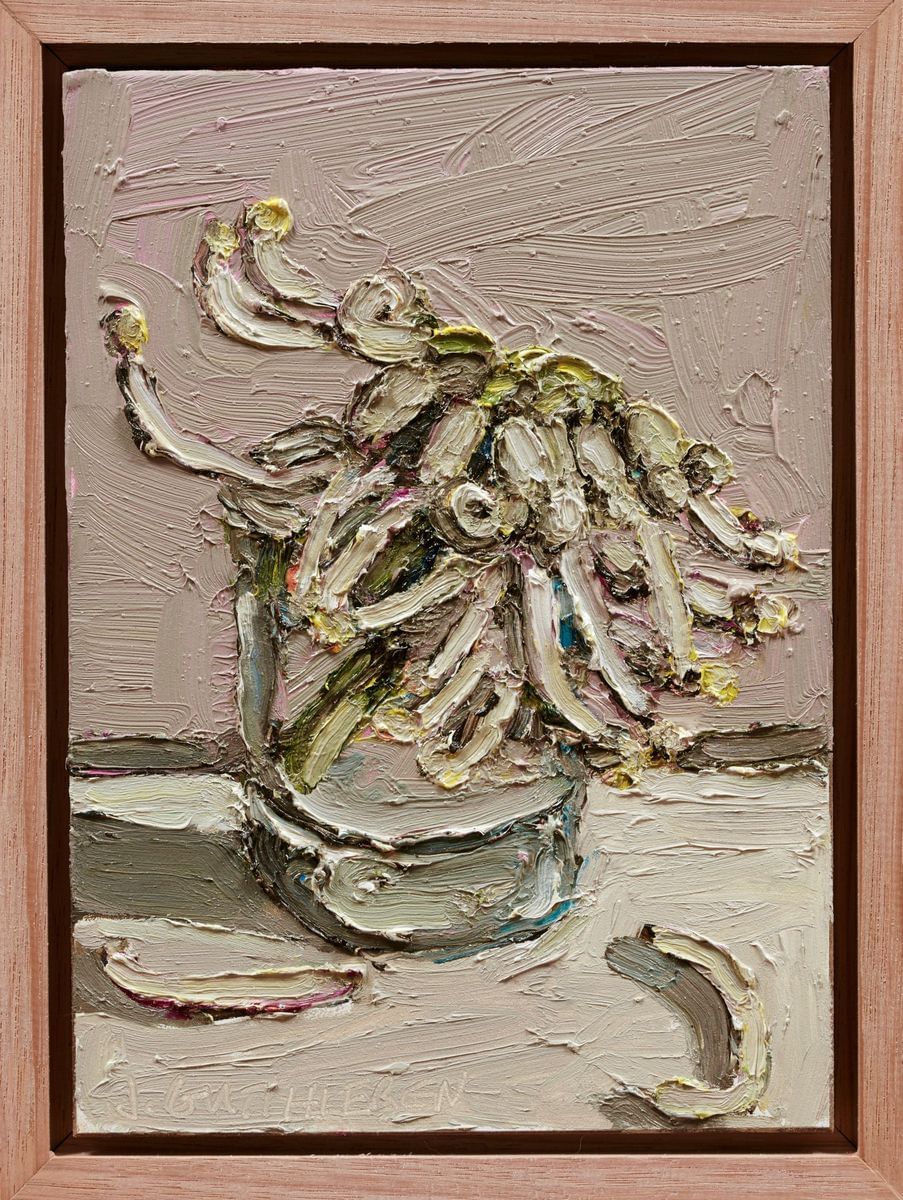

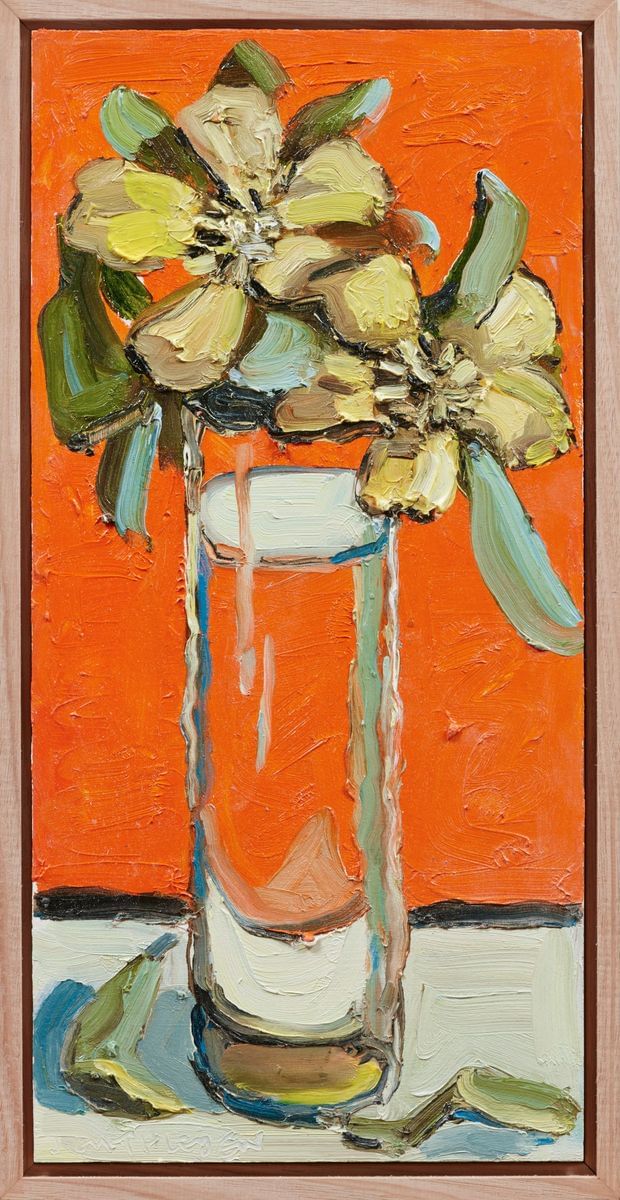

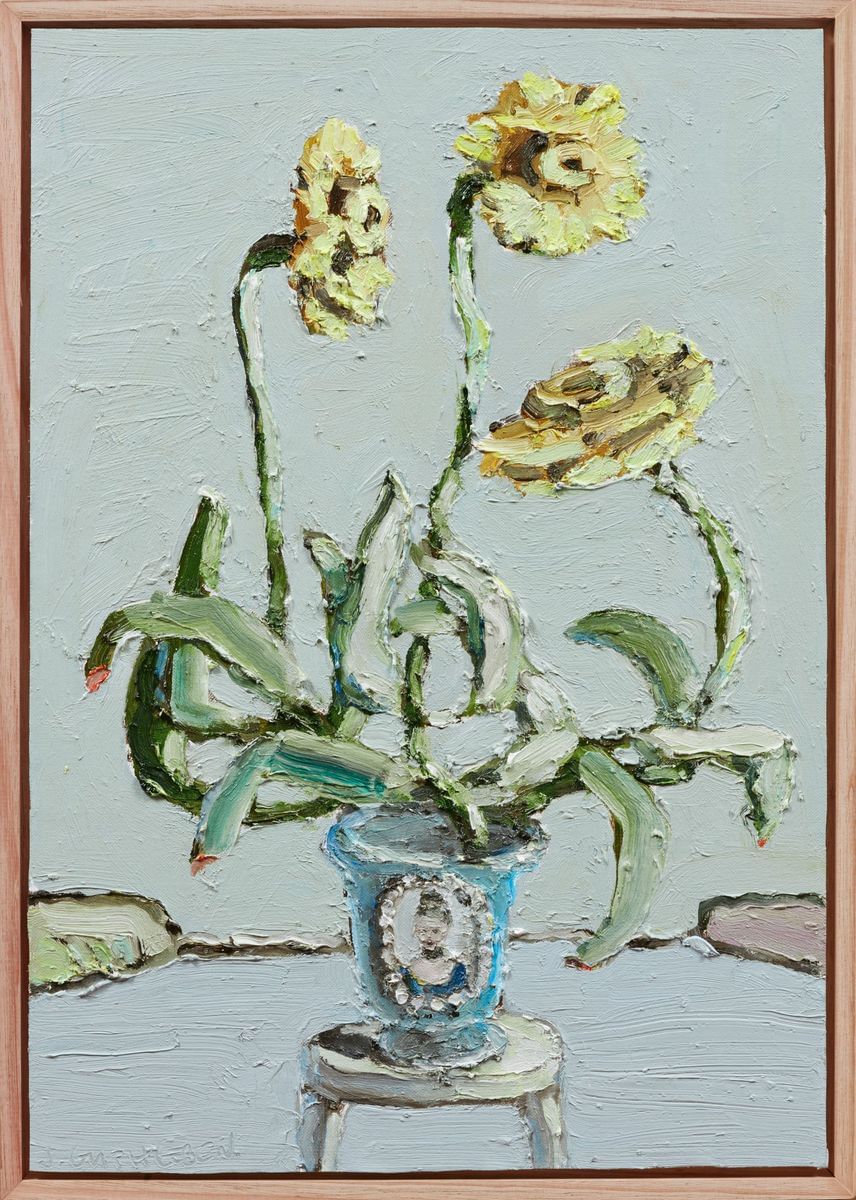

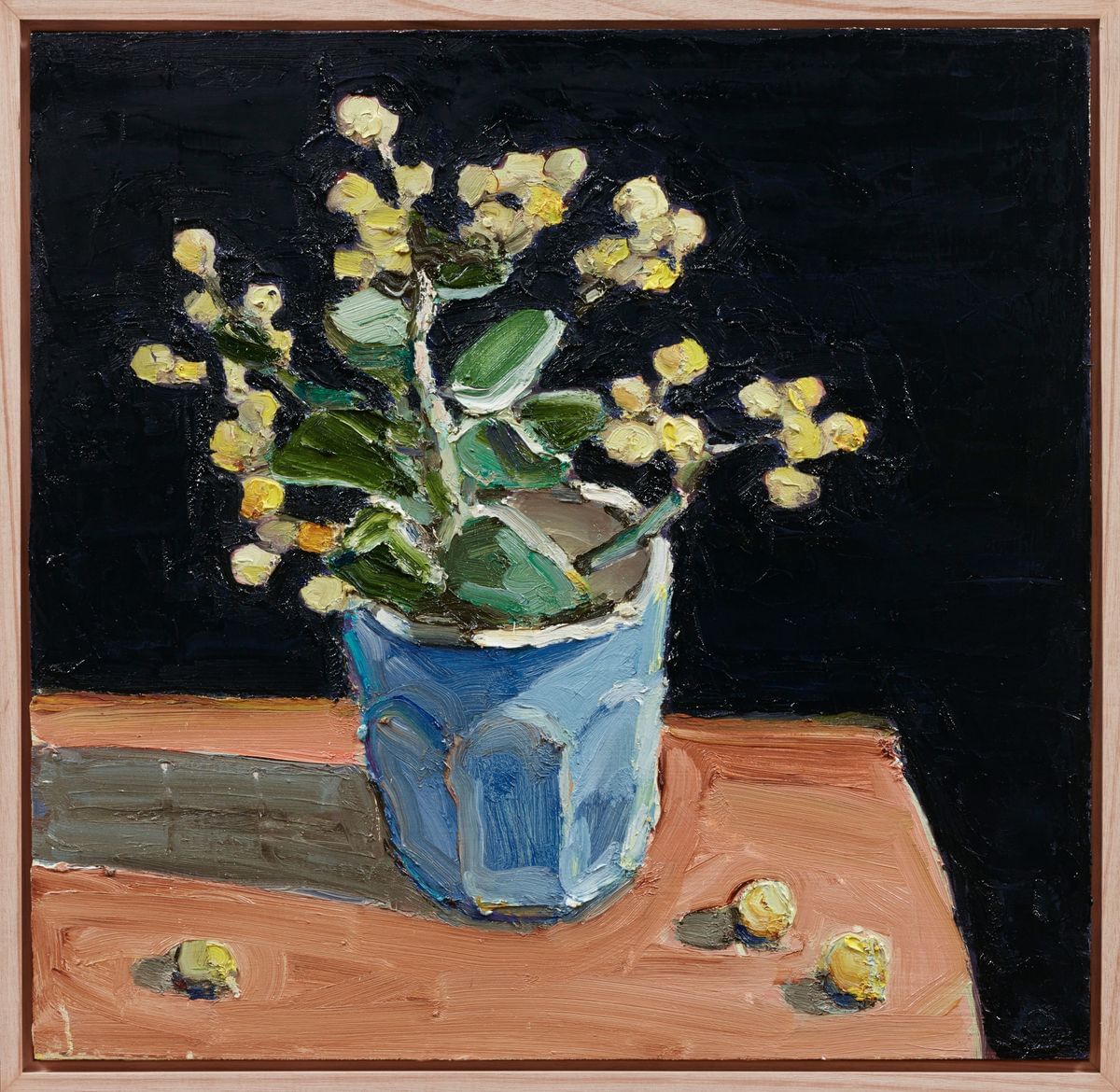

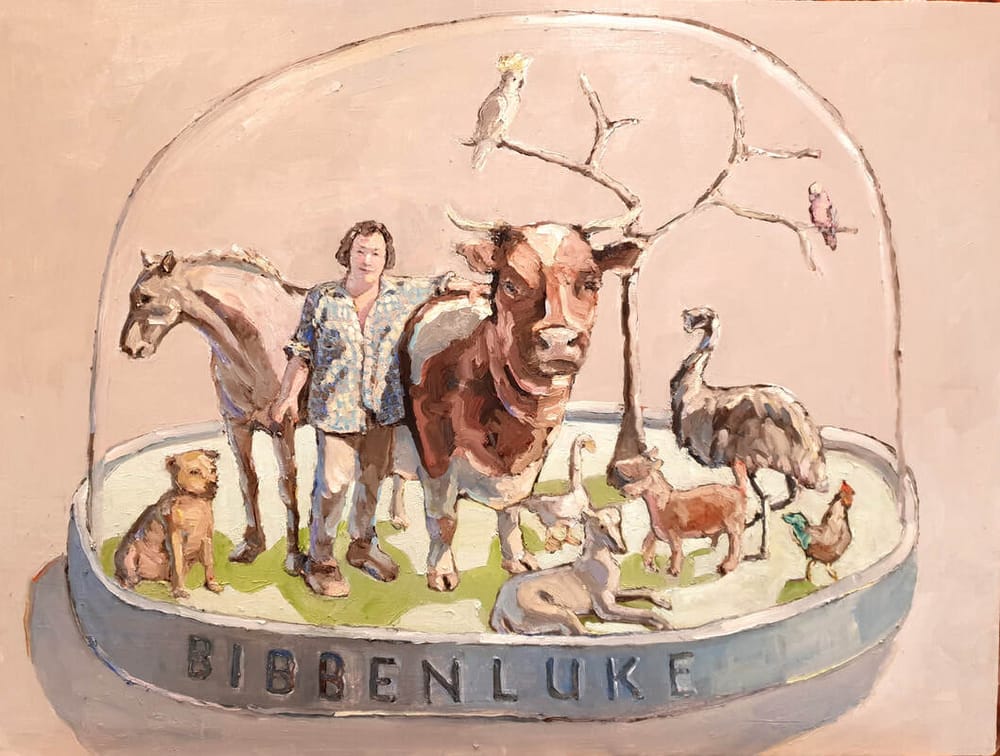

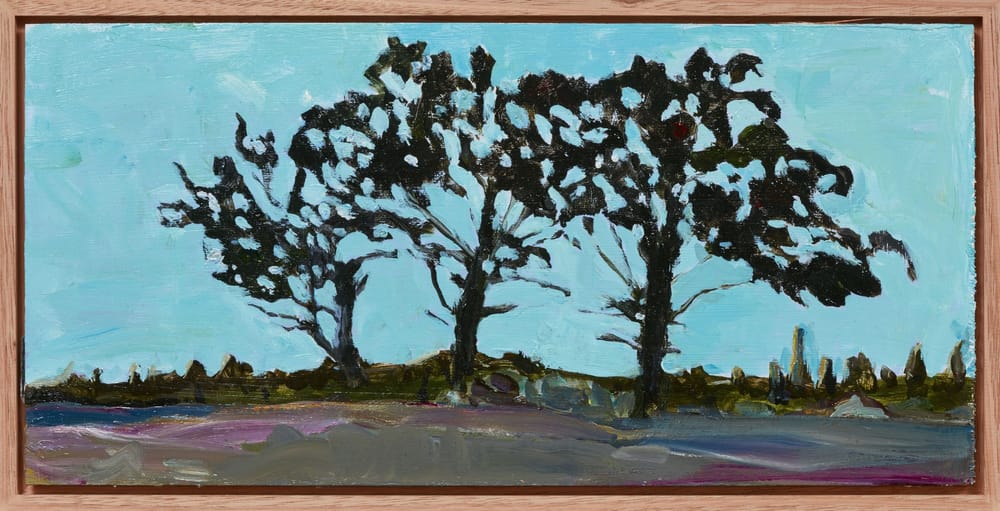

This exhibition continues Guthleben’s ongoing project based on Banks’s botanic encounters from the 1770 voyage. Working from the list of species that Banks collated from his voyage, Guthleben has recreated imaginary floral arrangements, landscapes and collections of flora from 250 years ago. If a painting captures a moment in time, these works aim to pause the clock at 1770, before the advent of the new colony and the dramatic changes to the environment that came with colonisation. Works such as What Banks Saw, and Florilegium, a 3.6 metre panorama, are mythical places where flora abounds in one verdant never-ending scene. Impossibly large arrangements such as Florilegium Arrangement with Dark Emu Wallpaper and Coastal Arrangement at Bustard Bay 2021 show the bounteous nature of the landscape and suggest how it is seen through European eyes.

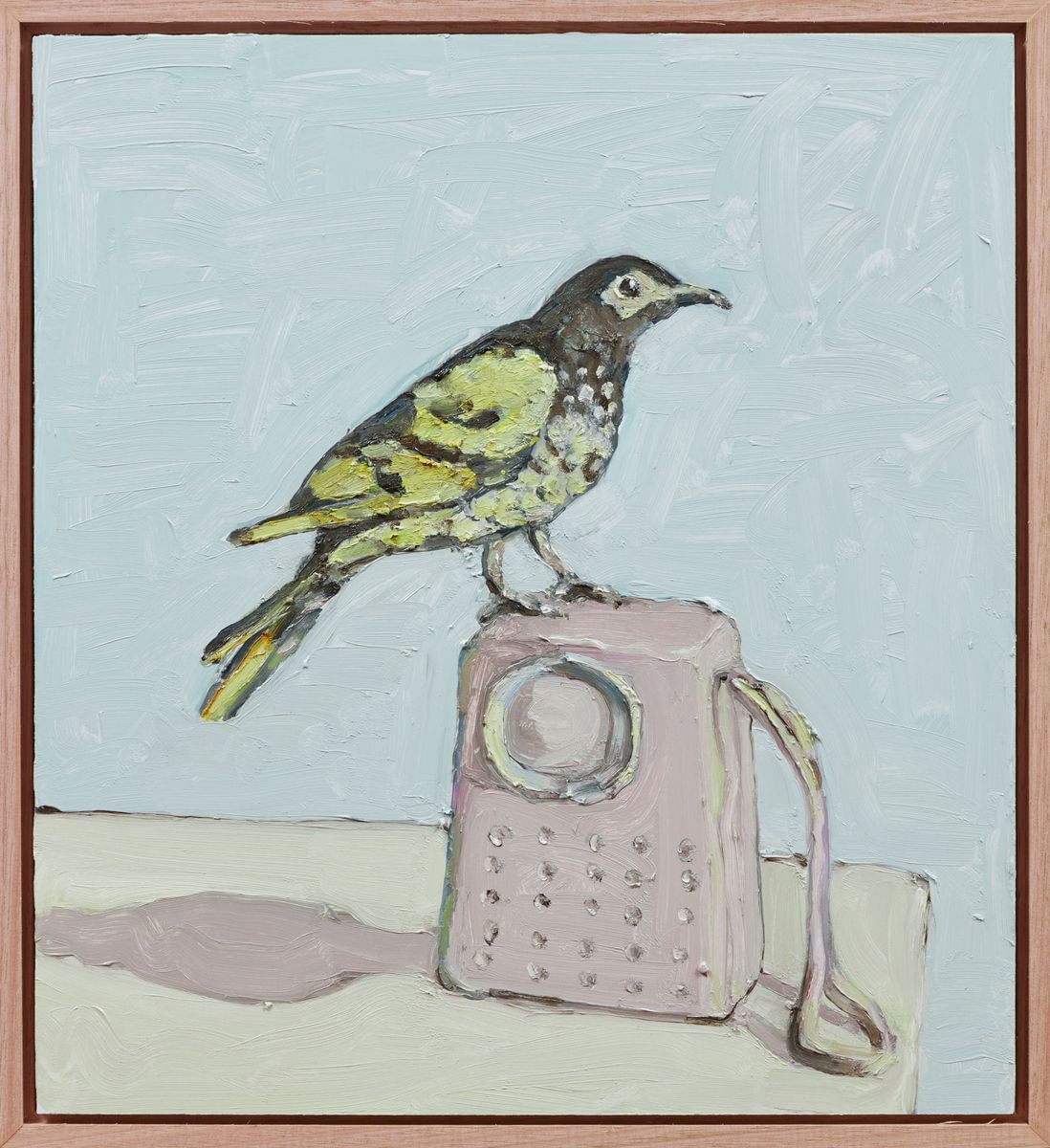

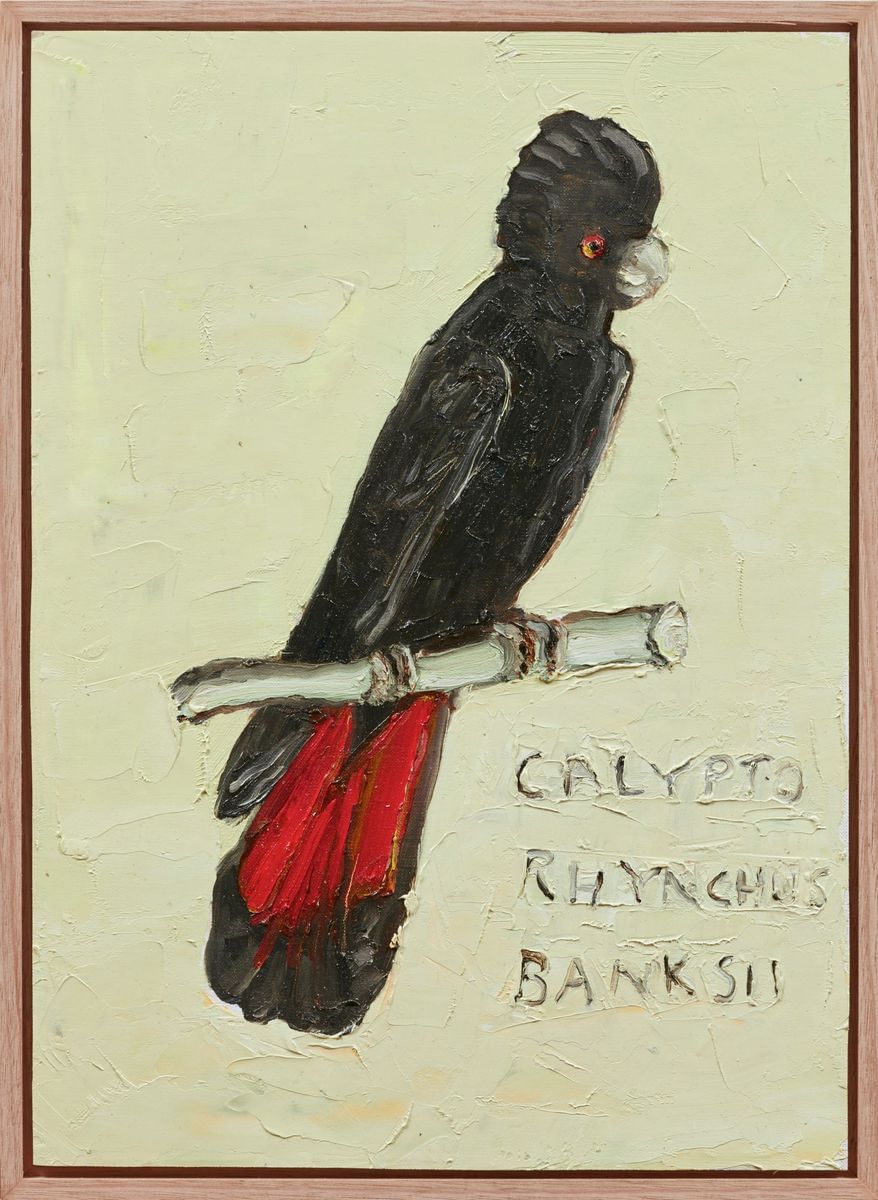

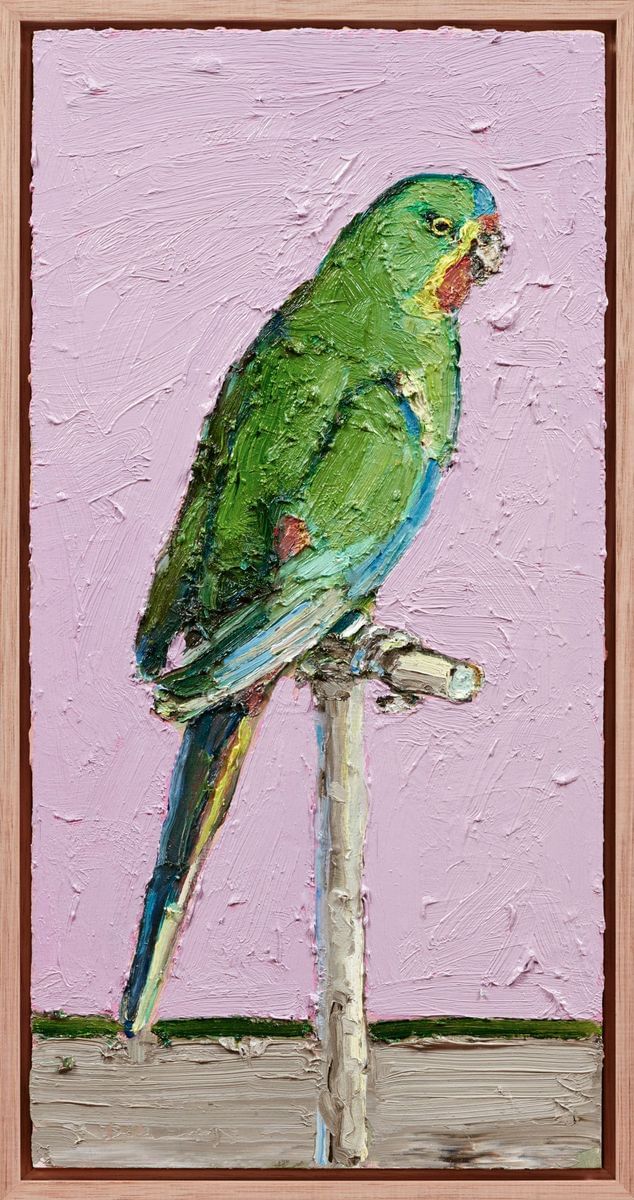

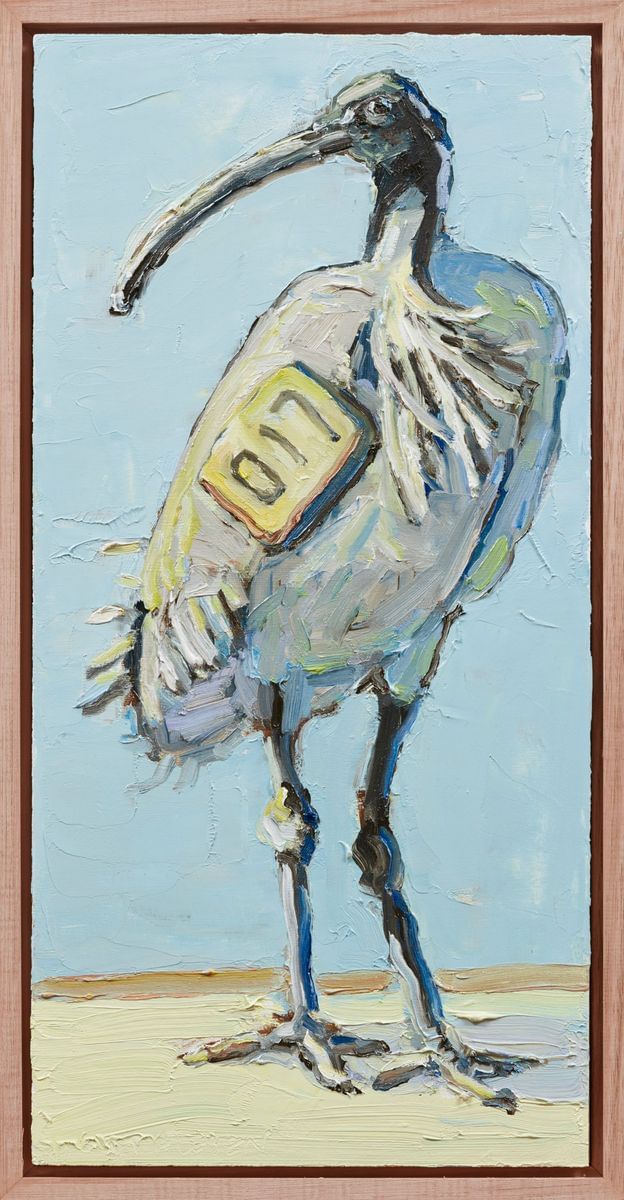

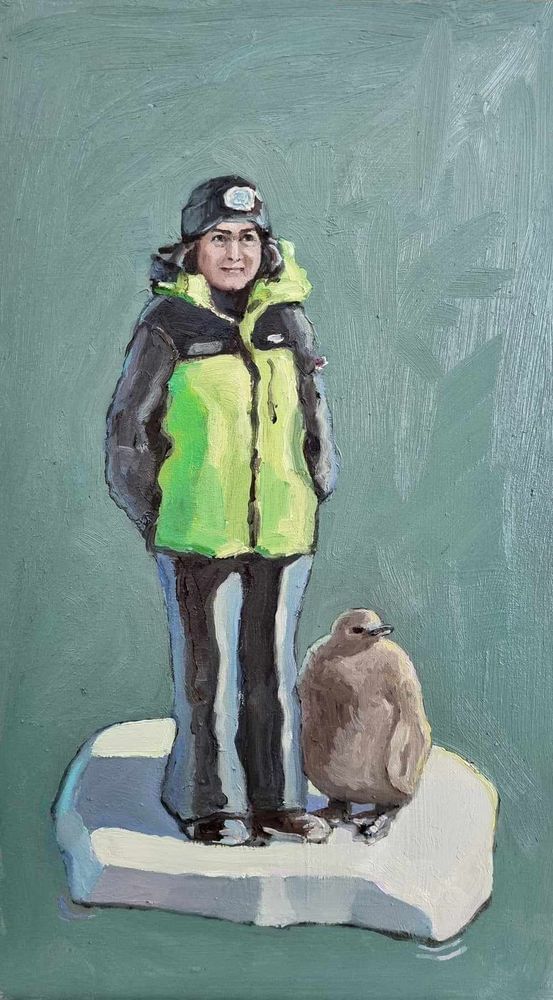

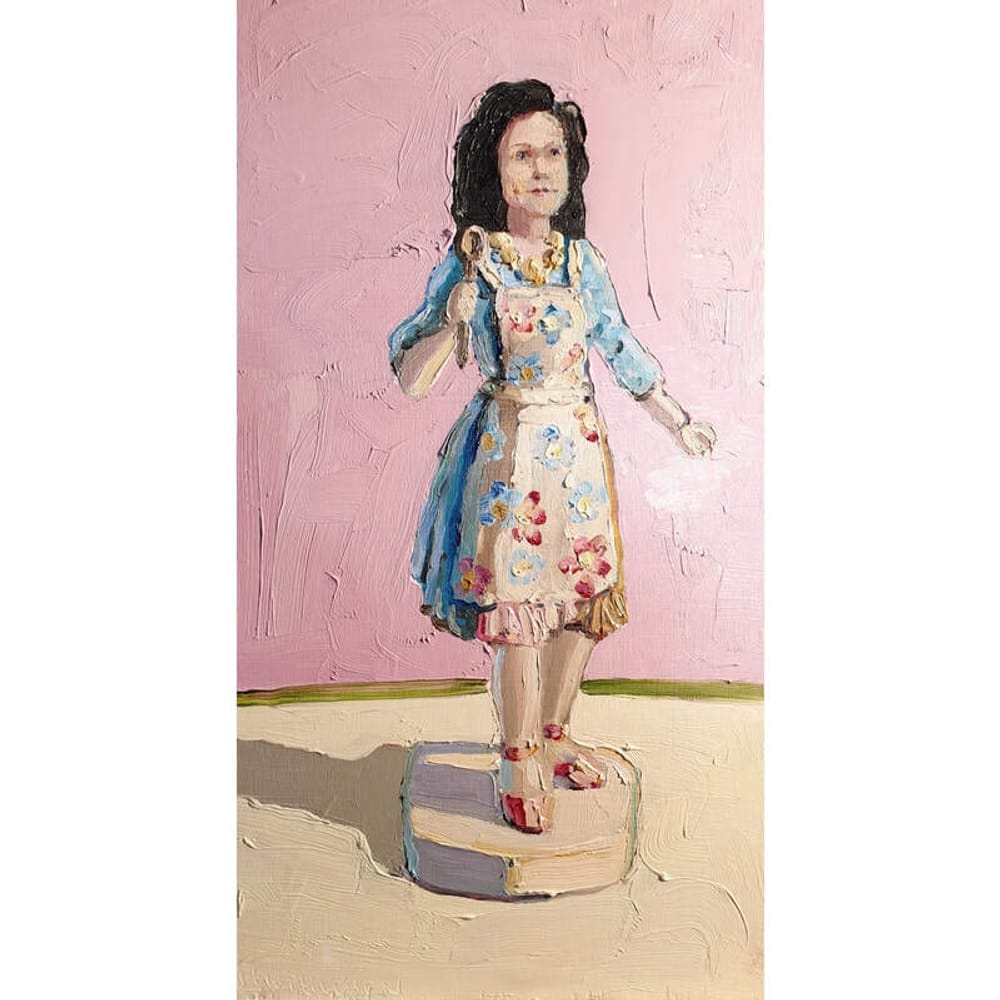

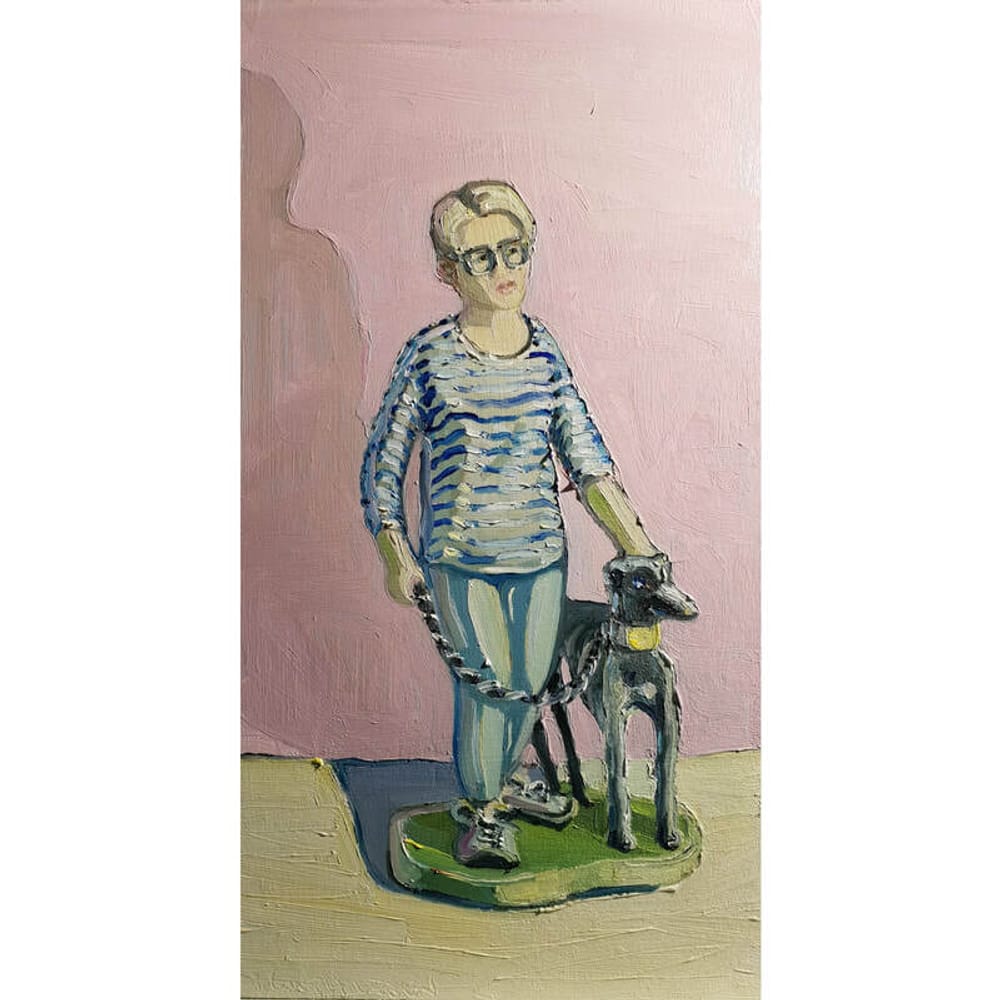

The exhibition also includes some other personal works, such as the large bird paintings, White ibis with wing jewellery, the Regent Honeyeater works, and a family portrait the Portrait of Ellen. Each of the works harks back to Banks’s voyage in that they each derive from the impacts of colonisation. The exhibition also includes studies in preparation for the larger works.

The exhibition title, Florilegium (pronounce flori – lee – gium), is a term given to a collection of writings or literary extracts, or to the visual records of a collection of plants. Like a botanical name, it comes from the Latin; from flos (flower) and legere (to gather). It is also the name of the beautiful book of Banks’s engravings project first published just 40 years ago.

Jane Guthleben, July 2021

Guthleben would like to acknowledge traditional owners whose way of life was immediately impacted by the 1770 encounters, and catastrophically changed by the subsequent colonisation in 1788. Banks, later head of the Royal Society, was hugely influential in promoting the continent’s virtues for a future penal settlement. Now, after 200 plus years of settlement, the flora and fauna he encountered is under pressure from dramatic changes in land use, population growth and climate change.

Through still life paintings of indigenous flowers, birds, and insects, Guthleben uses the traditions of vanitas and its messages of the transience of life to present a painted vernacular that spans humour, kitsch, and historical and environmental themes.

She reinterprets the delicate floral masterpieces of Dutch Golden Age painting by amping up the colour and light in response to the Australian environment and emphasising the texture and diversity of indigenous flora in brushy impasto.

Jane Guthleben studied a Bachelor or Fine Arts with honours at the University of New South Wales in 2015. Guthleben has been a finalist in the Archibald Prize (2020), Mosman Art Prize (2019, 2012), the Portia Geach Memorial Portrait Prize (2023, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018), Eutick Memorial Still Life Award (2018), Ravenswood Women's Art Prize (2019, 2017) and the Fisher's Ghost Art Prize (2015) among others.